Someone Always Has to Kiss Something

As you ramp up your holiday promotions, consider that maybe it’s not the best idea to suggest relationships are a transactional enterprise in which physical affection is bartered for luxury goods.

I don’t know…maybe—just maybe—that drains the fun and innocence and magic out of the season. Or maybe not. Maybe by now we’ve all just accepted that the holidays have absolutely nothing to do with religious tradition or the importance of family and everything to do with cultural peer pressure that makes people fear falling short when it comes to gifting. (Go us!)

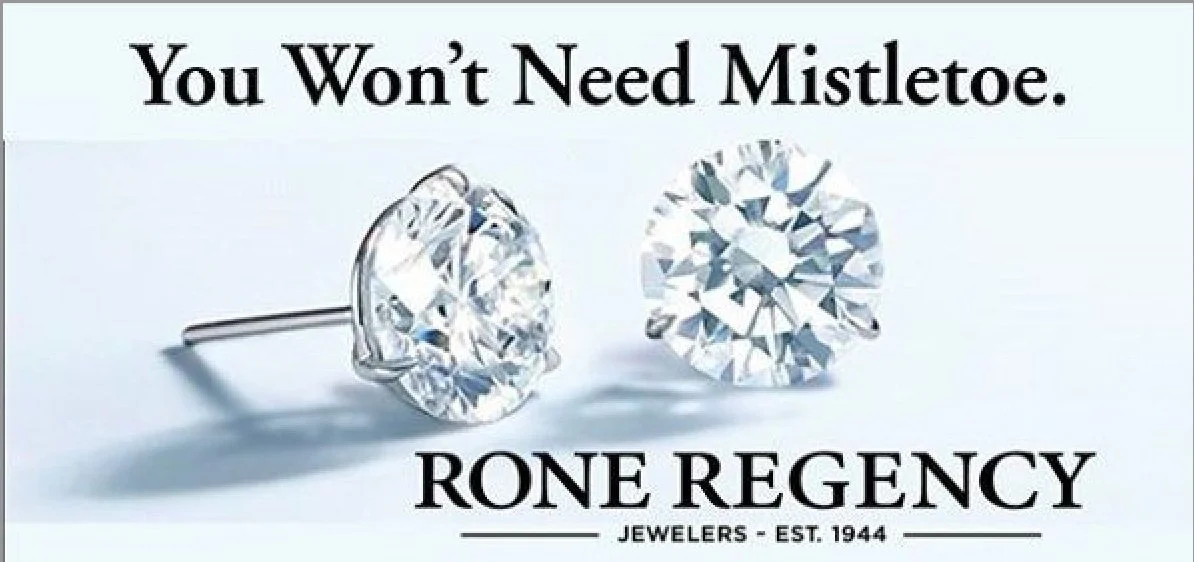

Perhaps you feel like this jewelry ad is just trying to be cute. Or perhaps you feel—as I did when I drove past a billboard with this on it—that it implies a certain view about relationships, a view that is cynical and disrespectful and outdated.

I’m sharing this not only because it’s fun to judge questionable messaging, but also because it speaks to a loud, ongoing feud between those who believe advertising should speak into social issues and those who think advertisers should just accept the world as it is, shut up, and sell.

The former tends to argue that advertisements—if only because of their relentless volume—are a part of cultural discourse and thereby influence the opinions people have about themselves and the world. They point at a phenomenon such as how the glorification of certain beauty standards contributes to depression, body dysmorphia, and disordered eating, and then they say, “See? And the same is true about…[insert the issue]. It has to be. Because we’re endlessly bombarding the audience with an idea and at a certain point some of them are going to have to think it means something.”

The other side says…“Shut up and sell. Meet people where they are. Stop talking about a ‘better future.’ Stop appropriating matters of politics and human rights in order to pitch products. If you want to ‘be the change,’ then go do that. But you volunteered to be a fluffer for capitalism, so get on your knees and quit pretending to be so damn high-minded.”

OK. Cool. Now that we’ve drawn up these acrimonious factions within advertising, I’d like to suggest that neither side wants to win. In fact, they need each other to sustain the industry.

The act of creating any narrative or representation of life—especially when run through the trials of a corporate sign-off process—involves an explicit acknowledgement of a worldview.

To get some idea of what the explicit view of the “Mistletoe” ad might’ve been, here’s an imaginary re-creation of its production process…

The jeweler’s marketing team starts planning. They get into it. They get so into it, in fact, that they create a dumb character archetype like Bourbon Bob: He’s worked his way up at an insurance company for twenty years, makes $300,000 a year, and generally doesn’t want to be bothered by anything because his life is disappointing enough.

During the holidays, Bourbon Bob just wants to sit in a chair, watch college football, sip from a bottomless glass of Weller, and, whenever the camera cuts to the cheerleaders, indulge nostalgic memories of youthful indiscretions.

Oh, Bourbon Bob gross. Bourbon Bob real gross.

But he’s the jeweler’s target market. He’s one of the few people who’s willing to throw down $1,000 to $10,000 for earrings he saw on a billboard. His understanding of his wife’s taste, were he forced to articulate it, amounts to “Uh, something shiny and expensive.” This is to say, he’s so crippled in his ability to express affection that he falls back on obvious gestures that take the form of big-ticket items.

That’s Bourbon Bob, and there’s no way the jeweler is going to risk Q4 results trying to change him. And so the jeweler tells an agency, “Make me something Bob will like, something that connects with the way he views the world.”

The strategy team—a rag-tag group of freelancers the agency pretends are staff—takes a break from writing LinkedIn posts and comes up with something along the lines of: Bourbon Bob wants a gift that’s a safe bet and requires almost no thinking, and he’s not afraid to pay for it. He wants a gift that, no matter how hammered and casually racist he gets at dinner, enables him to say he’s done his duty as breadwinner.

The team passes that off to the copy and art team along with the note, “Oh, and by the way, we only have one image, and it’s of diamond earrings.”

A few days, and eighteen pitch decks later, we have, “You won’t need mistletoe.”

This is what it looks like to “accept the world, shut up, and sell.” It involves creating work with cynicism, projecting the most selfish and base qualities onto its audience. And while it might successfully get Bob to shell out his bonus, it’s also why so many people in advertising prefer to write about making the world a better place: Because it’s too depressing to think that their life will be spent pandering to Bourbon Bob.

And so a lot of the “better world” ads seen on the awards circuit are part of a collective effort to deny what most of advertising really is. If everyone were to accept advertising on these terms, the world at large would hate it even more. In this way, the “better world” idealists serve to advertise the advertising industry as something other than a group of sweaty, desperate mercenaries trying their best to be trendy.

This is why so many creatives openly describe projects as “work that can go in the portfolio” and “work that will get me paid.” To have a portfolio full of, say, “Buy One, Get One” banner ads for Target—to essentially say to the world, “This is my contribution to the world”—is humiliating to the average person who sincerely studied the craft of writing, design, or videography.

And so, to keep going, they have to do the “better world” stuff. The have to believe in something bigger and more magical than strikethrough pricing.

If you can’t understand that during the season of Santa and Hallmark movies, I’m sorry. It might be too late for you.